Inside Project Ara, Google's Lego-like Plan To Disrupt The Smartphone

Inside Project Ara, Google's Lego-like plan to disrupt the smartphone

Rafa Camargo is playing ping-pong. Thirty minutes ago, he placed the world's most interesting smartphone into his jacket pocket. Now that jacket and its precious contents are lying on the floor. Right under my nose.

Camargo is the lead engineer on Project Ara, Google's attempt to build a smartphone that lets you swap out its parts like Lego blocks -- just by popping them on and off. Slide in a couple of speaker modules if you're throwing a party, insert an additional battery if you'll be out on the town or even slot in exotic modules like glucometers (for diabetics) or sensors to measure air quality. While we've recently seen LG attempt to build a modular smartphone with the G5, these Ara snap-on concepts are the kind of features you'd never find on a normal phone built for mass-market adoption.

With an Ara smartphone, you can snap on new parts.

Sean Hollister/CNETCamargo and I have just shared a five-minute shuttle ride to Google Building CL5, where he's promised to give me a closer look at the phone he'd demonstrated minutes earlier to an ecstatic crowd at Google's I/O developer conference.

After several failed demonstrations in the past, he says a consumer version of the phone will ship next year. Moreover, while manufacturing will no doubt be subcontracted out to the likes of a Flextronics or Foxconn, Google will design the phone itself. That's a change from its Nexus phones, where it relied on hardware partners such as LG, Huawei and Samsung.

The result -- if it hits its target 2017 delivery date to consumers -- will be a user-upgradeable handset with the potential to totally upend the smartphone market as we know it.

The dream: A truly customizable phone

In the three years since work first started on Ara, the modular phone has always seemed like a pipe dream, and Google has always treated it that way. It's been part of the company's ATAP division -- Advanced Technologies and Products -- a skunkworks explicitly tasked with turning such fantasies, like sensors you can swallow, into consumer reality.

Rafa Camargo holds up an earlier Ara prototype in 2015.

James Martin/CNETBut Ara made promises it couldn't keep. In years past, the modular tech failed repeatedly in demonstrations. The prototype was all set to start a pilot program in Puerto Rico. And then, all of a sudden, it wasn't, with barely an explanation. There were tweets from the project's team that suggested ATAP was rethinking how the components linked together.

On top of that, the team's original head, Paul Eremenko, left the company. Then, in even more of a blow, Regina Dugan, the leader of ATAP itself, departed Google for Facebook. There, she'll run something called Building 8, a similar effort focused on creating experimental hardware.

So after Friday's announcement, you would be forgiven if you thought the past few months had been a magic trick of misdirection. Because Project Ara was quietly evolving while we were all wondering if it was even still breathing.

An hour before the ping-pong match, in a jam-packed session at Google's developer conference, Ara's key innovation finally works. Camargo places his phone on a table, and says the magic words. "OK Google, eject the camera." When the phone's camera pops out of its socket, all by itself, the crowd erupts with applause.

But then Camargo slips the phone into his jacket pocket -- presumably to thwart handsy journalists like me from learning too much. I worry that he won't show me the phone at all, that I'll never be able to tell if his successful demo on stage was an exception to the rule. When he drops his jacket and picks up the ping-pong paddle, a tiny part of me wonders what would happen if I were to sneak a peek at the phone.

But when we finally sit down in a conference room to talk about the future of Ara, it turns out I had nothing to fear: Camargo repeats the magic words and out pops the camera.

The modular phone is real.

Scaled back

Ara isn't quite the same project that captured my imagination. It's still pretty exciting, but the idea has been notably scaled back.

Originally, Project Ara would have let you build your own phone like computer enthusiasts build their own desktop PCs, choosing all the parts yourself. Ara could have been the last phone you'd ever need: just swap out the processor and cellular radios when newer ones come along, and you'd be up to speed. Google would provide the "endoskeleton" -- the equivalent of a PC's motherboard -- and an ecosystem of hardware partners would have done the rest.

The current prototype of the Project Ara Developer Edition. Camargo assures us the final version will be thinner and more "beautiful."

Sean Hollister/CNETBut the new Project Ara isn't designed to let you swap out core components like the processor. Now they're all built right in.

"When we did our user studies, what we found is that most users don't care about modularizing the core functions," Camargo explains. "They expect them all to be there, to always work and to be consistent."

"Our initial prototype was modularizing everything...just to find out users didn't care," he adds.

So instead of letting you build your own future-proof phone, the new Ara is about giving you a phone with mix-and-match features you can't get anywhere else.

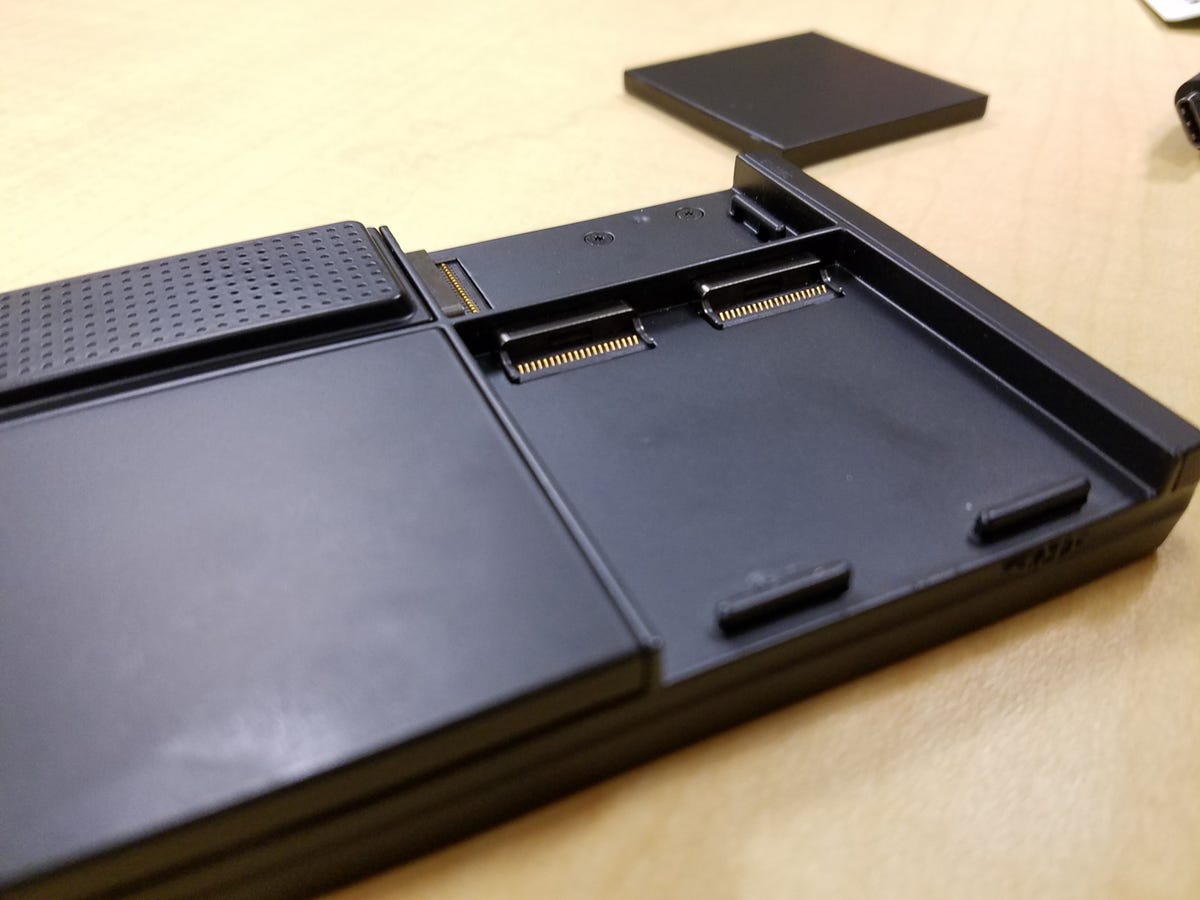

The bigger module slot can hold two 1 x 2 modules, or a single larger 2 x 2 one.

Sean Hollister/CNETThe Ara advantage

When the Project Ara Developer Edition ships this fall, it will come with four modules to start: a speaker, a camera, an E-Ink display (like the one you'd find on an Amazon Kindle e-reader) and an expanded memory module.

Those might not sound all that exciting, but they're all things that even high-end smartphones don't necessarily do well. If you don't like the single, easily muffled speaker on your Samsung Galaxy or wish your iPhone had more storage space, you're generally out of luck.

"[Phone manufacturers] say, here, you have 3 millimeters to make a speaker, and you're stuck with your sound quality," says Kevin Hague, a VP with Harman Audio. Harman is working with Google to prove that a dedicated speaker module might be one of many reasons to buy an Ara phone.

The Project Ara team has already modularized the battery technology. Pull out the second battery, and it keeps working.

Sean Hollister/CNETAnd with Ara, you're not limited to just one: you'll be able to turn Ara into a boom box with multiple speakers and multiple batteries snapped into the phone's six module slots. With even the standard integrated battery, Camargo says we should expect a full day of battery life from the consumer version of Ara, and he estimates that adding a single modular battery should boost that by roughly 45 percent.

But cameras, batteries and speakers are just the low-hanging fruit: the Ara team believes its platform will open the floodgates for third-party hardware developers to build all sorts of products that never would have made it into smartphones before -- from a wireless car key fob (Camargo says he has a working prototype) to a one-use pepper spray dispenser. BACtrack, a company specializing in alcohol breathalyzers, is also on board.

"We know that people are going to build crazy stuff, and that's OK," says Blaise Bertrand, ATAP's head of creative and marketing chief. "In fact, we're looking forward to this."

Medicine could be a particularly interesting market, where people are willing to pay for technology that might improve their lives, but only a small percentage of people have any given need.

"The glucometer example: I'm lucky, I don't need it, so I don't care about that module. But if you're a diabetic, it's probably essential in your life," says Camargo. "Nobody's going to build a phone with that integrated."

When I think about awesome technology that not everyone needs, some of Google's other ATAP projects also come to mind, like the Project Tango depth-sensing camera or the Project Soli gesture-sensing radar. Camargo won't say yes or no, but suggests Ara could help:

"You see all these technologies that are very applicable to mobile but have a hard time making it into the next flagship phone because it's a high risk. You're selling 80 million of that thing, and you don't want to make a mistake [...] I expect them all to see modules."

In other words, instead of trying to figure out how to build the world's best phone camera that fits into a phone that people can actually afford, camera makers could focus on building the world's best phone camera, period -- and sell it for a premium to boot.

Serious business

The prototype Ara camera module. Imagine swapping it out for one with a wider-angle lens, or upgrading it entirely in a few years.

Sean Hollister/CNETWhile a lot of the details aren't sorted out yet -- like how much modules will cost -- Google seems serious about building out Ara. As of last month, the Ara team is no longer part of the ATAP skunkworks; it now reports directly to Rick Osterloh, the head of Google's new hardware division and a recent transplant from Motorola.

"We can get all the resources and funding we need to make it a business," says Richard Wooldridge, a leader on the Ara project.

Wooldridge, who coincidentally ran supply chain operations for Osterloh back at Motorola, says Ara will make it easy for just about anyone to build modules, whether they're a "bedroom student" or a fashion brand looking for a way to physically interact with consumers.

Not only will Google provide instructions and developer test beds, it'll help module makers navigate the challenging process to get those gadgets certified by federal regulatory agencies if need be.

"We want to create a hardware ecosystem on the scale of the software app ecosystem." - Ara lead engineer Rafa Camargo

GoogleWooldridge sees Google launching an online store to sell the modules, and a marketplace for consumers to swap them with each other. (To protect against counterfeits, Google will have its own certification program for Ara modules, and Ara phones will reject ones that haven't been approved.)

"We want to create a hardware ecosystem on the scale of the software app ecosystem," says Camargo.

But the biggest sign of Google's sincerity may be this: the company will be building the first consumer version of Ara all by itself. While every previous flagship Android handset has been built by one of Google's partners, most recently Huawei and LG, Ara is the first handset that Google has ever designed from scratch.

When it arrives next year, the Ara team says the basic version should cost around the same amount as other premium smartphones, with performance on par.

A modular future

Even if Ara is no longer "the last phone you'll ever need to buy," that doesn't mean it couldn't become more PC-like in the future. Camargo says the technology to swap out processors and radios still exists. "We have the capabilities to do that, so things will evolve."

Google's Greybus -- the digital backbone that allows these modules to seamlessly interface with each other and the Android operating system -- can already transfer data at speeds of up to 11.9 gigabits per second. (That's faster than USB, and Carmago says it uses one-third the power.)

As the technology stabilizes, says Camargo, Google also intends to let other companies build Ara frames -- not just the modules, but entire Ara computers with module slots.

Camargo playing ping-pong.

Sean Hollister/CNETIn fact, there's nothing saying Ara devices need to be phones. "In my lab, I have configurations that don't have anything to do with a phone and cannot make a phone call."

During that ping-pong game, some 45 minutes ago now, I couldn't help but notice that Camargo plays a bit too aggressively. His shots sailed just past the end of the table. But when it comes to Ara, Camargo has a lighter touch.

"We really have to bring it to consumers, we have to make it attractive, we have to make them understand it," says Camargo. He needs to land this shot.

CNET's Gabriel Sama and Richard Nieva contributed to this report.

Source

Tags:

- Inside Project Ara Google S Lego Like Plan To Disrupt British Trade

- Inside Project Ara Google S Lego Like Plan To Disrupt In Spanish

- Inside Project Ara Google S Lego Like Plan To Protect

- Inside Project Ara Google S Lego Like Plan To Nourish

- Inside Project Ara Google S Lego Like Plan B

- Inside Project Ara Google Scholar

- Inside Project Ara Google Search

- Inside Project Ara Google Sign

- Inside Project Ara Google Scholar

- Inside Project Arachne

- How To Trim Corrugated Tin Out On Inside Project

- Inside Project Zorgo Mask